Diving into the realm of chemistry reveals a fascinating journey through the behavior of substances in various environments, with one of the most intriguing questions being: how do ionic compounds like potassium nitrate behave in water? When potassium nitrate dissolves in water, it dissociates into its ions, setting the stage for a remarkable transformation. This process not only alters the compound’s physical state but also its electrical properties, raising the question: Does potassium nitrate conduct electricity in water?

Understanding the conductivity of potassium nitrate in an aqueous solution offers insights into the broader world of electrolytes and their critical role in numerous applications, from industrial processes to biological systems. As we explore the enigmatic nature of KNO3 electrical conductivity, we uncover the essential mechanisms through which ionic compounds transform simple water into a conductive medium, highlighting the intricate dance of ions that power so many of the systems we rely on every day. Join us as we unravel this ionic journey and delve into the science behind potassium nitrate’s electrifying abilities.

The Composition of Potassium Nitrate

Potassium nitrate (KNO3) is a classic example of an ionic compound formed by the electrostatic attraction between positively charged potassium ions (K⁺) and negatively charged nitrate ions (NO₃⁻). In its solid state, KNO3 forms a crystalline lattice in which each K⁺ ion is surrounded by nitrate anions and vice versa. This arrangement maximizes the ionic attractions, conferring a high melting point (334 °C) and making it a stable, white powder under ambient conditions. The nitrate ion itself is planar and trigonal, with resonance-stabilized bonds between nitrogen and oxygen atoms. The overall Molar mass of KNO3 is approximately 101.10 g/mol, reflecting the combined masses of K (39.10 g/mol), N (14.01 g/mol), and three O atoms (3 × 16.00 g/mol).

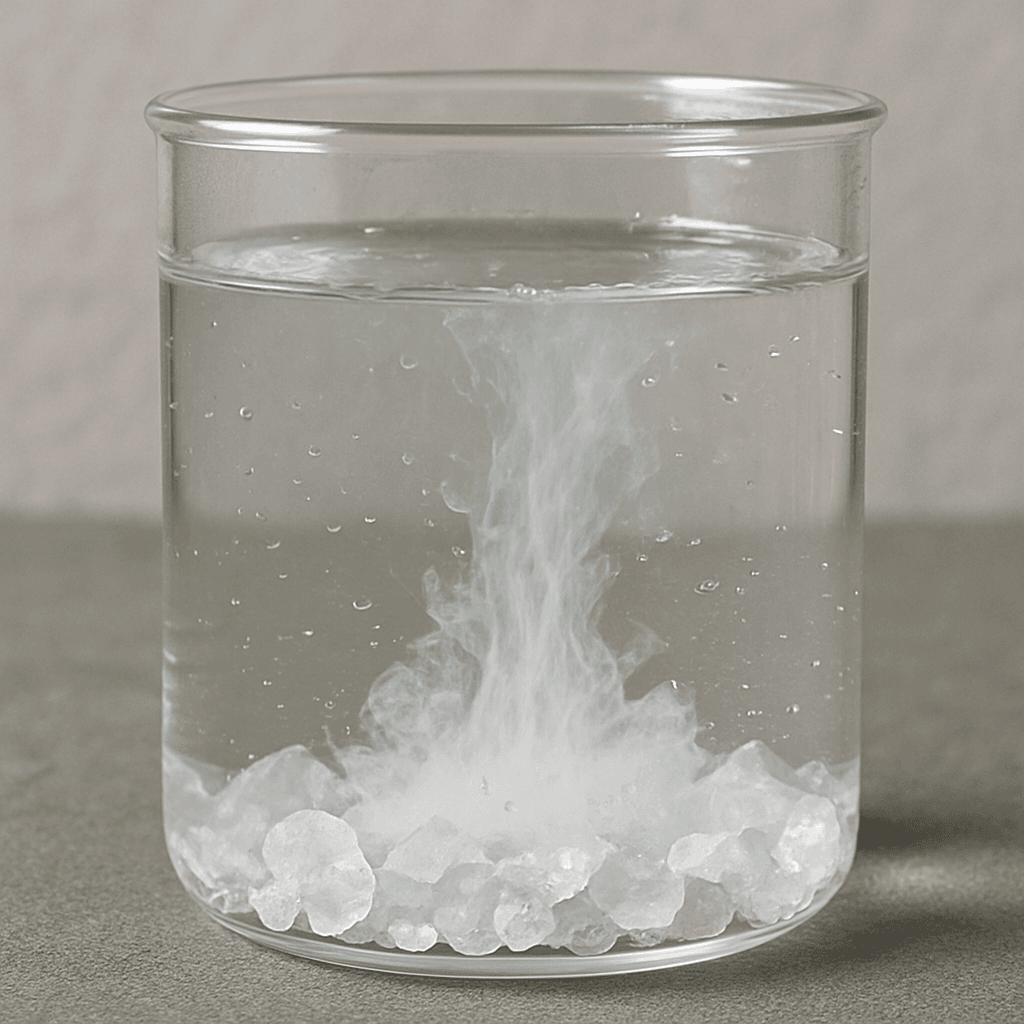

Under dry conditions, potassium nitrate remains a poor electrical conductor because its ions are fixed in the lattice and cannot move freely. However, its solubility in water—about 32 g per 100 mL at 20 °C—allows the lattice to break apart through potassium nitrate dissociation in water. Once dissolved, KNO3 exists as freely moving K⁺ and NO₃⁻ ions, setting the stage for ionic conductivity. This dissolution process is endothermic, absorbing heat from the surroundings to overcome lattice energy and hydrate the ions. The hydration shells that form around each ion stabilize them in solution, ensuring they remain separated and mobile. These dissolved ions are the key to transforming a non-conductive solid into an effective potassium nitrate electrolyte.

Conductivity of Ionic Compounds in Water

Ionic compounds conduct electricity in aqueous solutions by virtue of their ability to dissociate into charged particles, or ions. When a substance like potassium nitrate dissolves, the cations and anions migrate toward electrodes under an applied electric field, creating an electric current. In this sense, does potassium nitrate conduct electricity in water? Indeed, it does: as a strong electrolyte, KNO3 fully dissociates into K⁺ and NO₃⁻, making the solution capable of supporting charge flow. The term “strong electrolyte potassium nitrate” underscores its near-complete ionization compared to weak acids or bases that only partially dissociate.

Potassium nitrate aqueous solution conductivity depends on factors such as ion concentration, temperature, and ion mobility. As concentration increases, more charge carriers are present, boosting conductivity until ion–ion interactions begin to retard mobility. Temperature elevation typically enhances conductivity by reducing solution viscosity and increasing kinetic energy, allowing ions to move faster. Conductivity is measured in siemens per centimeter (S/cm), and typical values for moderate KNO3 concentrations (0.1 M) range around 0.012–0.015 S/cm at 25 °C. These values demonstrate that KNO3 solutions are effective at carrying current, making them useful in applications like calibration standards for conductivity meters, buffer solutions in electrochemistry, and specialized batteries.

مقارنة مع المركبات الأيونية الأخرى

To appreciate the electrical behavior of potassium nitrate, it helps to compare its performance with that of other common ionic salts such as sodium chloride (NaCl) and calcium chloride (CaCl2). In general, the conductivity of an ionic solution is a function of both the number of ions produced per formula unit and the mobility of those ions. NaCl, for example, dissociates into two monovalent ions (Na⁺ and Cl⁻), while CaCl2 yields three ions (one Ca²⁺ and two Cl⁻). Consequently, a 1 M CaCl2 solution typically shows higher conductivity than a 1 M NaCl solution due to its greater ionic strength.

Compared with NaCl, a 1 M KNO3 solution produces only two ions (K⁺ and NO₃⁻), leading to a lower ionic strength relative to CaCl2 but similar to that of NaCl. However, mobility differences between ions come into play: potassium and sodium ions have comparable ionic radii and hydration enthalpies, so KNO3 and NaCl solutions at equal molarity exhibit similar conductivities. The nitrate ion, being larger and less hydrated than chloride, may move slightly faster, giving KNO3 a marginal edge under certain conditions. Overall, while strong electrolyte potassium nitrate conducts well, its conductivity at a given molarity falls between that of NaCl and CaCl2, offering moderate performance in electrochemical applications.

Biological Implications of Potassium Nitrate’s Conductivity

Potassium nitrate’s ability to transform water into a conductive medium extends beyond the laboratory, influencing biological and ecological systems. In soil science, nitrates serve as a vital form of nitrogen for plant nutrition. The conductivity of soil water—enhanced by dissolved nitrates—affects root membrane potentials and ion uptake mechanisms. When potassium nitrate is added as a fertilizer, it increases soil ionic strength and electrical conductivity, which can improve nutrient transport to plant roots. However, excessive conductivity can lead to osmotic stress, hindering water uptake and plant growth.

In biomedical contexts, potassium nitrate finds use in dental care products such as desensitizing toothpaste. The mechanism hinges on its ionic nature: KNO3 electrical conductivity allows potassium ions to diffuse into dentinal tubules, decreasing nerve excitability and reducing sensitivity. Moreover, potassium nitrate’s conductivity underpins its use in physiological experiments as a benign electrolyte, maintaining ionic balance in artificial bodily fluids. Understanding how ionic compounds conduct electricity helps researchers optimize concentrations to mimic natural environments without causing cytotoxicity, showcasing the intersection of chemistry and biology in practical applications.

Conclusion: Unraveling the Mysteries of Potassium Nitrate’s Electrical Conductivity

Potassium nitrate’s journey from a stable ionic crystal to a highly conductive aqueous solution exemplifies the fundamental principles of electrolyte chemistry. By fully dissociating into K⁺ and NO₃⁻ ions, KNO3 transforms plain water into a medium capable of sustaining electrical currents, confirming that potassium nitrate does conduct electricity in water is a resounding yes. Its moderate conductivity, influenced by concentration and temperature, positions it between NaCl and CaCl2 in performance.

Exploring potassium nitrate’s conductivity not only illuminates its practical uses in calibration, fertilizers, and dental care but also deepens our understanding of how ionic compounds conduct electricity. From industrial to biological settings, the electrodynamic behavior of KNO3 underscores the vital role of ions in powering the processes that sustain both technology and life.